The Tiny Bird that Could Save an Ecosystem

High Country News, 1 July 2024

“Imagine you’re a phalarope — a female Wilson’s phalarope, to be precise, Phalaropus tricolor. Your tiny, fragile body fits in the palm of a human hand and weighs little more than a double-A battery. You have long, dark legs, a white belly and blue-gray wings that lighten into a ruddy color at your neck. Your face is mostly white, with a dark cap and a black mask leading to a slender, pointed beak.

Your appearance makes you unusual among birds: Female phalaropes are larger and more colorful than their male counterparts. You look good, and you know it; you choose your mates, competing aggressively with other females, and you practice polyandry, taking multiple partners.

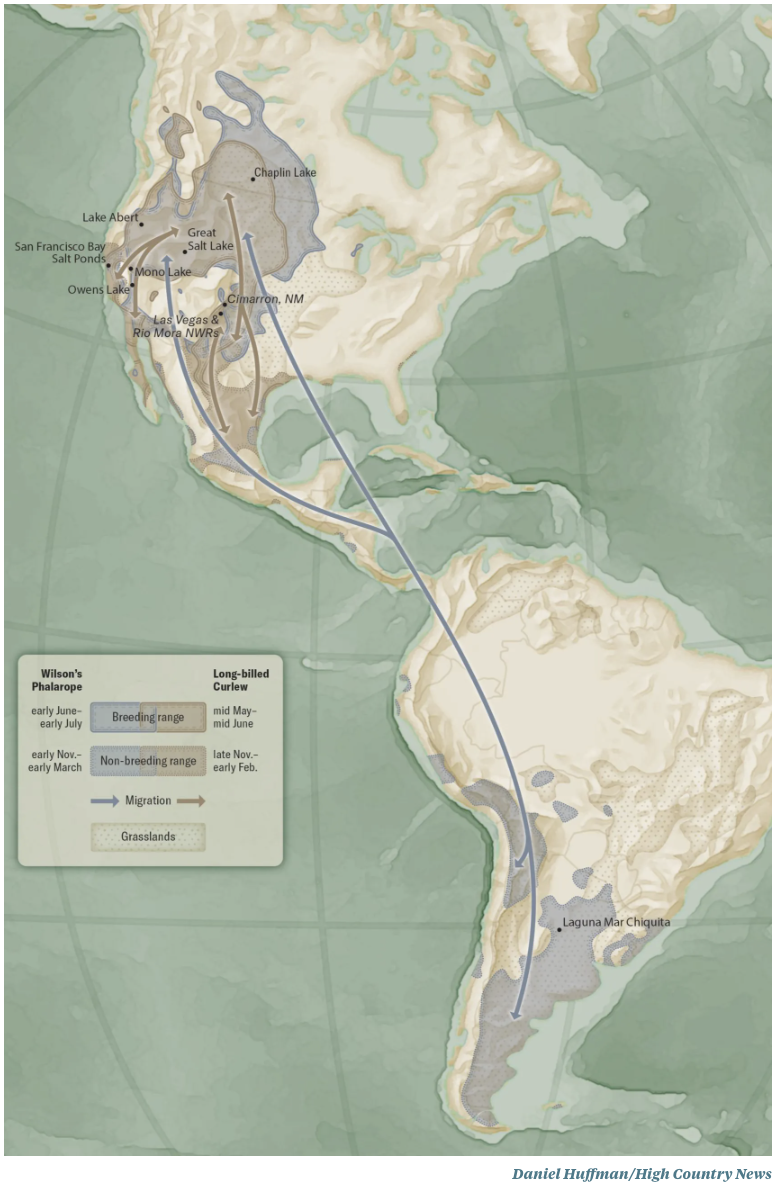

You’re exceptional in another way, too: You’re the only bird species that migrates across the entire Western Hemisphere, stopping primarily at inland salt lakes — “freakish habitats,” as ornithologist Margaret Rubega put it.

In spring, you nest in the prairies surrounding Saskatchewan’s Chaplin Lake. Then, you fly south to the U.S. Great Basin, seeking out places like Utah’s Great Salt Lake, Oregon’s Lake Abert and California’s Mono Lake to chow down on flies and their larvae to double your weight before migration. You might be best known for your unusual hunting technique: Sometimes you spin around in the water, shoveling it backwards with your lobed feet to force any fly larvae suspended in the lake up to the surface.

Once you’ve bulked up and molted, you fly south to South America for the austral summer.

But what if you flew to one of your salt lakes, and it wasn’t there?”

Podcast interview with KUOW/NPR’s The Wild: https://www.kuow.org/stories/caroline-tracey-how-this-tiny-bird-could-save-salt

High Country News, 1 July 2024

“Imagine you’re a phalarope — a female Wilson’s phalarope, to be precise, Phalaropus tricolor. Your tiny, fragile body fits in the palm of a human hand and weighs little more than a double-A battery. You have long, dark legs, a white belly and blue-gray wings that lighten into a ruddy color at your neck. Your face is mostly white, with a dark cap and a black mask leading to a slender, pointed beak.

Your appearance makes you unusual among birds: Female phalaropes are larger and more colorful than their male counterparts. You look good, and you know it; you choose your mates, competing aggressively with other females, and you practice polyandry, taking multiple partners.

You’re exceptional in another way, too: You’re the only bird species that migrates across the entire Western Hemisphere, stopping primarily at inland salt lakes — “freakish habitats,” as ornithologist Margaret Rubega put it.

In spring, you nest in the prairies surrounding Saskatchewan’s Chaplin Lake. Then, you fly south to the U.S. Great Basin, seeking out places like Utah’s Great Salt Lake, Oregon’s Lake Abert and California’s Mono Lake to chow down on flies and their larvae to double your weight before migration. You might be best known for your unusual hunting technique: Sometimes you spin around in the water, shoveling it backwards with your lobed feet to force any fly larvae suspended in the lake up to the surface.

Once you’ve bulked up and molted, you fly south to South America for the austral summer.

But what if you flew to one of your salt lakes, and it wasn’t there?”

Podcast interview with KUOW/NPR’s The Wild: https://www.kuow.org/stories/caroline-tracey-how-this-tiny-bird-could-save-salt